Regulatory Networks

Regulatory interactions in DNA are commonly portrayed as gene regulatory networks. These diagrams typically show genes as nodes, with arrows indicating activation and bars indicating repression. They may also summarise the regulatory logic governing each gene. Davidson and colleagues’ work on sea urchin development (Davidson2006?) remains perhaps the most impressive.

This is from Fauré et al. (2006), showing part of the regulatory network controlling the eukaryotic cell cycle.

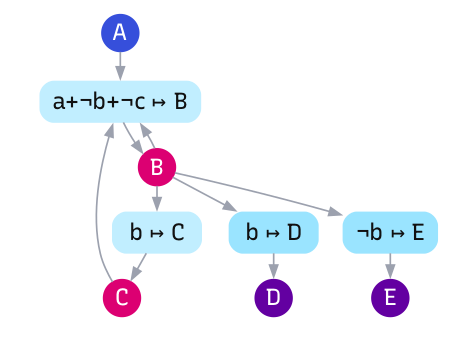

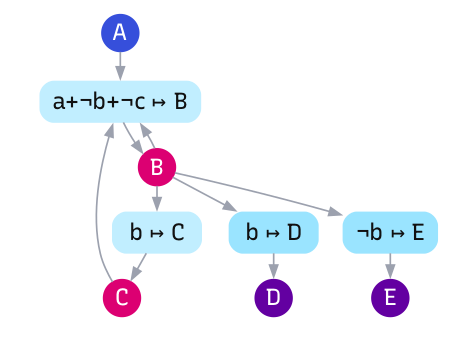

We can create similar diagrams for our AND programs. Figure 1 shows the regulatory network for tumbling behaviour. These are bipartite graphs, with two node types: genes (the coding regions) and elements (the stimuli, memory, and responses). We summarise each regulatory region’s logic as a single Boolean expression capturing all binding sites that region controls.

Our simple programming language can be translated to well-accepted and well-studied simplfication of gene regulation: the field of Boolean regulatory networks. Importantly, however, while this network summarises interactions between program expressions, this portrayal it is not equivalent to the program itself. Many different programs can produce the same network structure, just as many different DNA sequences can produce the same regulatory interactions.

We can distinguish three related things:

- A strand of AND code (the genome),

- The behaviour it produces (the phenotype),

- A regulatory network that provides a compressed representation of the code.

Ipmortantly, we don’t mutate the regulatory network directly. We mutate the AND code, which then a new regulatory network.

The same is true of real biological regulatory networks. Such diagrams are often presented as the gene regulatory network for an organism. But such diagrams are representations that have been constructed with particular aims in mind.

The relationship between AND code and its regulatory network is many-to-one.

Simplifications

I oversimplify here. Genes respond to various external factors beyond other genes, including co-factors. These don’t bind directly but bind transcription factors, changing their shape. The model captures the “spirit” of this interaction, rather than its precise nature. Environmental factors contribute to the combinatorial equation that turns genes on or off.