The way organisms are built is weird

Engineers routinely borrow ideas from biology. We have swimsuits like sharkskin and sticky-tape like gecko feet. But our borrowing is confined to the way things work, not how they are built. We might copy the structure of a gecko’s foot, but we don’t copy how that structure develops in a gecko embryo. This is because the way organisms are built is very strange.

Human construction is top-down: it starts with prefabricated parts, a plan, and someone to carry it out. A trip to IKEA captures these elements. Building that new set of drawers requires (a) a flat-pack of parts, (b) a fold-out manual, and (c) you.

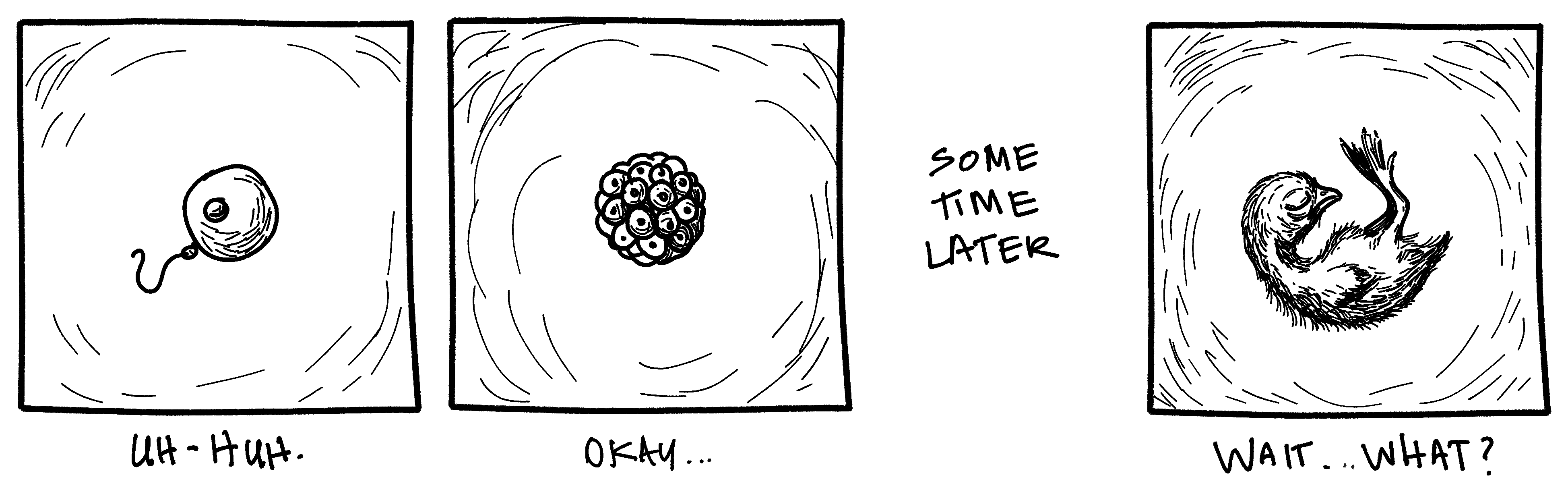

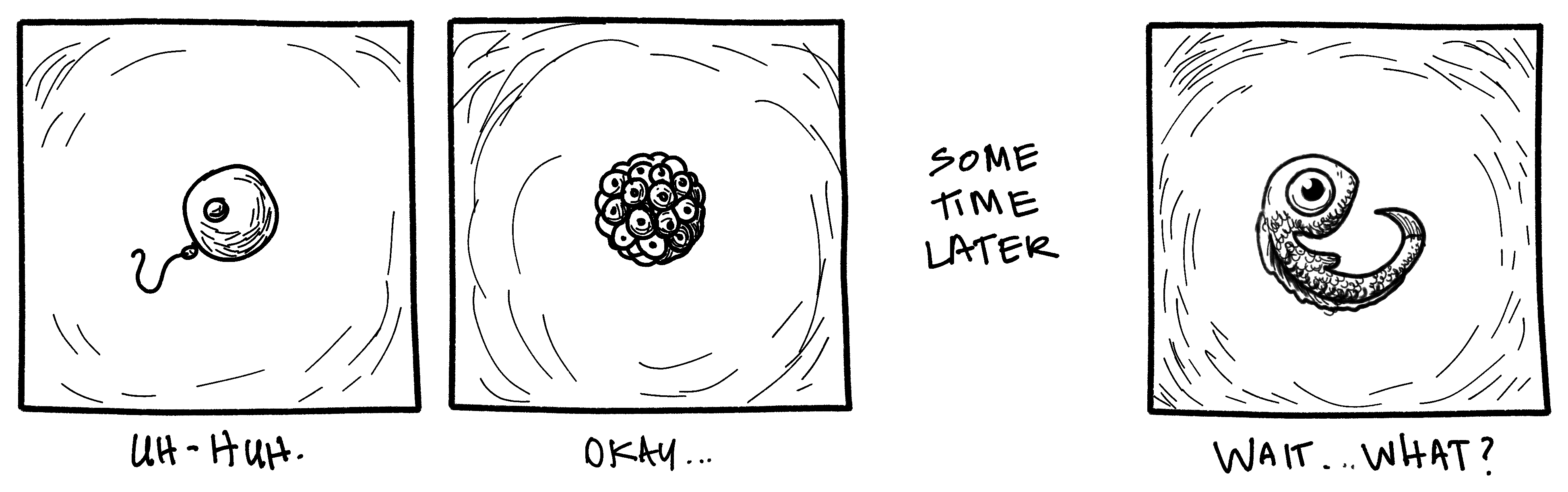

The construction of an organism, in contrast, looks nothing like this. There are no obvious instructions, no prefabricated parts, and no visible assembler. The creature just builds itself from the bottom up.

Consider how remarkable this process is

From a single cell and a suitable environment, a functioning organism emerges — with limbs, organs, and attitude. How does such complex order unfold from one tiny cell?

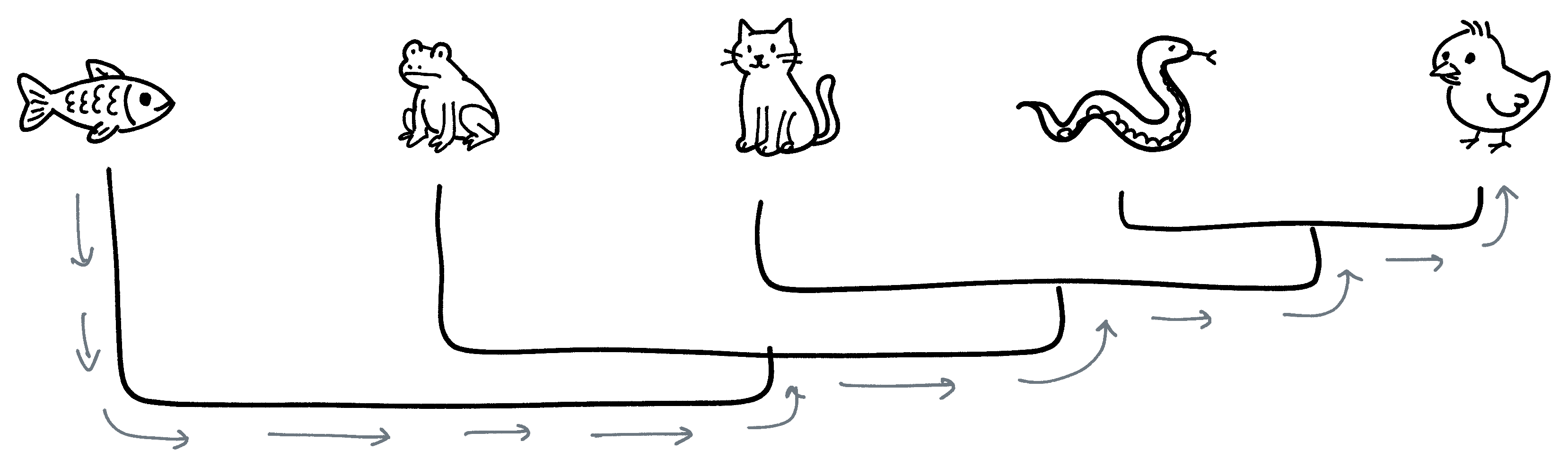

This method of construction is capable of producing a broad range of outcomes. Start with a different cell and you get a different, species-typical arrangement — fins, not wings; scales, not feathers. What guides the process to such diverse, specific outcomes?

Despite this diversity, some unifying process underlies how organisms construct themselves. A chick and a fish are very different. Yet they are connected by a continuous series of small, viable changes. How can such a complex process be modified gradually?

How does that work?

Despite the weird way organisms are built, we often explain the process in terms of human engineering. Here, DNA is cast as a plan—a “blueprint”, “instructions”, or a “program” for building the organism. An explanation of the features above might go something like this:

The DNA inside that first cell contains a tiny plan for building the organism. This plan specifies how the organism is built. Different plans lead to different organisms. Gradually modifying the plan allows a smooth transition between them.

There is, rightly, a good deal of criticism of such claims. In particular, it is thought that this engineering thinking, with its reliance on plans and instructions, overemphasises the role of DNA. Importantly, this focus on DNA is at the expense of other factors, such as the power of self-organisation, and the reciprocity of interaction between the organism and its environment.

The upshot of these criticisms is a rejection of engineering analogies—views that treat DNA as instruction-like are seen as deeply misleading, and should be abandoned altogether. But that is not our only option. Another approach is to endorse an engineering approach, and to see DNA as a bottom-up control system that exploits the environment and self-organisation. The challenge is to show how such a control system works, and to explore the consequences of this view for our understanding of development and evolution.

This website presents a series of models that explore this idea. I begin by showing how DNA can legitimately be thought of as a program (but not the kind you are thinking of). Then I show how such a program can help explain the puzzling features above, and how this view is compatible with seemingly contrary ideas—such as environmental plasticity, self-organisation, and even goal-directed behaviour.